(text)

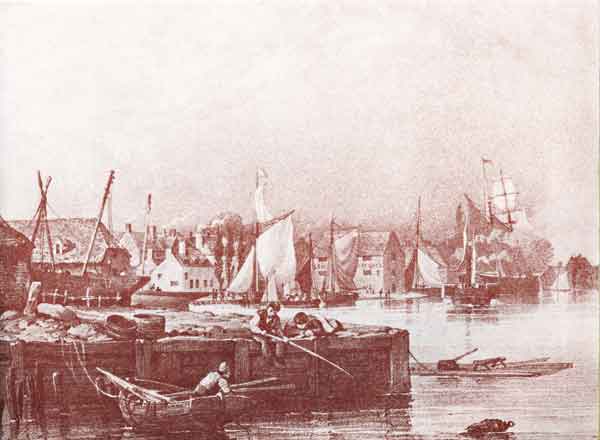

The Lymington River

Lymington Harbour about 1836

The Early Years:

Geographically, 'a drowned river valley', the Lymington estuary was

originally a tributary of the River Solent which flowed between Poole and

Chichester. Since the days of the Iron Age, Buckland Rings and Ampress

(550-100 B.C.) stand proof of the early importance of the river to which the

Romans gave the name, 'Full River.'

Some nineteen hundred years ago, the Emperor Claudius despatched his

General, Vespasian, to conquer Britain. After pacifying Kent, Vespasian

moved his legions to the Isle of Wight. Arriving at the western end of the

Island, he almost certainly crossed to the mainland from the most convenient

embarkation point which was later to become Yarmouth.

He disembarked at the Alaunian Wood (Alauna Sylva) or 'at the mouth of the

river Alainus' (Full River): almost certainly the river or creek of Limenton

(Celtic: limi = stream; ton = town). Here he attacked and reduced the

British earthwork fortress, now known as The Rings. From that desolate

battleground the view southward to the sea towards The Island, and to its

Jagged, needle-like rocks, would have been little different to that of

today; and on the slope of the hill near the river estuary, Vespasian would

have noted a settlement of British huts, clustered by the waterside: there,

too, sailing craft may have been moored to the nearby banks.

Man had not yet interfered with the course of the river which was then

wider, deeper and certainly navigable to above Ampress and probably beyond

Boldre, the tidal stream reaching as far as Brockenhurst. Lymington was a

port by the time that William the Conqueror handed the kingdom over to his

son.

Emerging from the Dark Ages, Lymington was granted its first charter in

about 1200, by the Second Earl of Devon, Baldwin de Redvers. Lymington was

one of the few English towns to have received its charter from its feudal

lord alone. At one time during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), the Port

of Lymington provided nine ships and 159 seamen to man them; the town

rivalled Southampton in importance and certainly out-shone Portsmouth.

French marauders frequently paced our streets; in 1370, Frenchmen, after

destroying Portsmouth, burnt Newtown, Yarmouth and Lymington. In 1545,

Claude d'Annebaut, failing to provoke Portsmouth with his fleet, sailed down

the Western Solent, burning villages and farms as he progressed. Since then

Lymington has had no cause physically to repel invaders. The modern pirate

is more subtle: noise, numbers and pollution require no less energy and

subtlety to resist.