Circumnavigation Planning

Many cruising sailors dream of making a circumnavigation. Very few of those actually get away and of those who do, maybe half fail to complete the voyage. It’s a daunting prospect and usually a pretty challenging experience too. Since 1977 some 27 cruising members in the RLym are known to have completed their circuit of the globe. In the following pages they give brief details of their voyage(s) and reflect on some of the high, and low, points along the way.

But before we get to their stories we have summarised some of the information which is common to everyone, with a look at the Earth’s weather systems, the most common routes, the types of boat and the additional gear which most ocean sailors will carry.

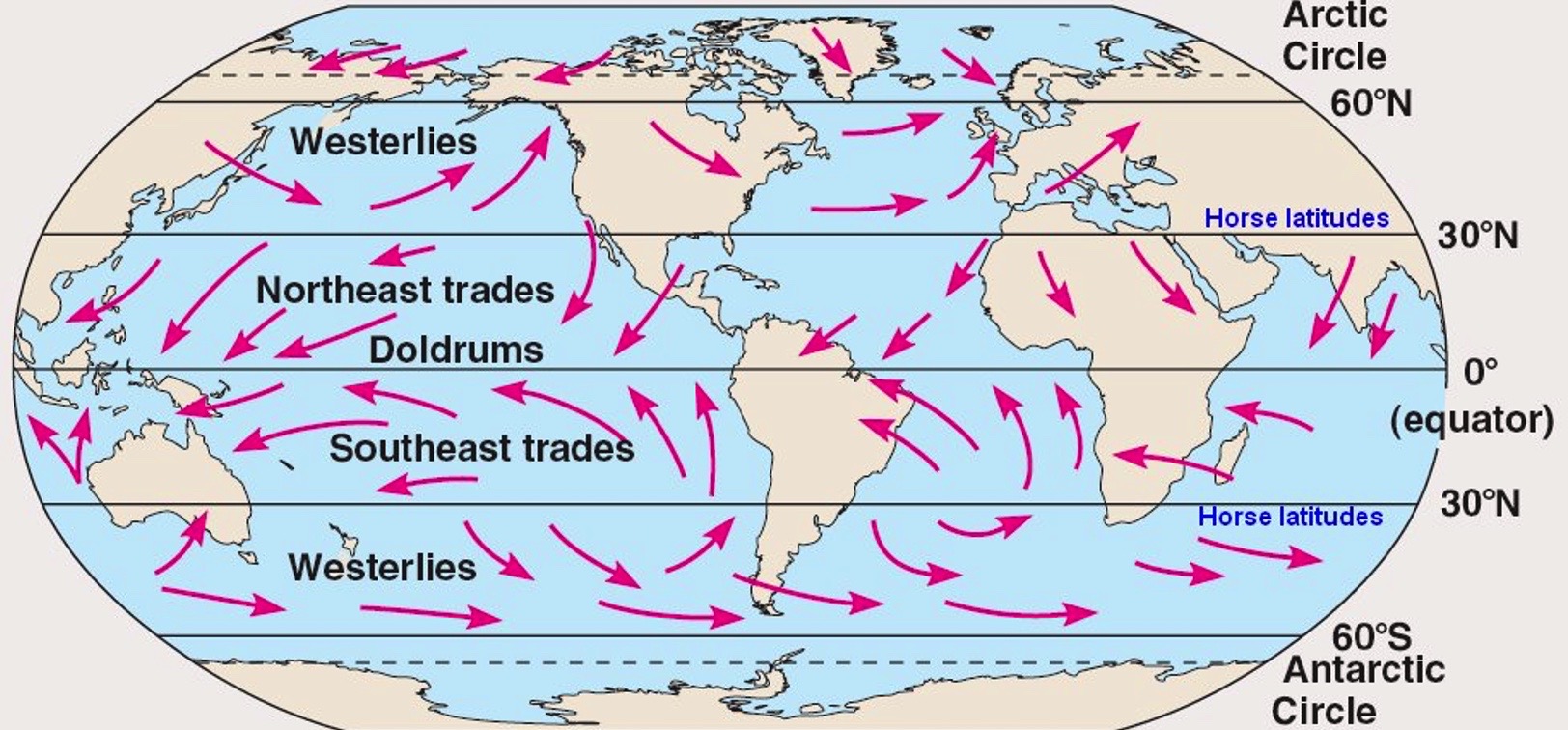

Weather Systems

Between roughly 30 and 60 degrees north and south of the Equator, Westerlies prevail carrying frequent depressions which regularly bring gales. In the northern hemisphere, the land masses of North America and Europe mean these westerly winds rarely exceed Force 10 (Storm) and are normally much lighter whilst in the southern hemisphere there is no land to impede their progress and the Westerlies become the wild Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties, with frequent winds of gale force and higher and mountainous seas.

Between these Westerlies. there are the Trade Wind belts, NE and SE, blowing at about 45 degrees towards the equator where they meet in the doldrums or ITCZ (Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone) – an unstable area just north of the Equator with mostly light and variable winds, but often no wind at all or strong winds under suddenly-forming, often isolated, towering clouds giving heavy rainsqualls and maybe lightning. In the Indian Ocean, wind flow gets a bit muddled by all the land, giving the SW Monsoon from May to October, north of the Equator.

The Trades are relatively benign winds, blowing mostly between F3 to F5 for months at a time and bringing mostly warm, sunny weather. But not all the time. In summer, these warm waters breed tropical revolving storms for up to six months of every year– the infamous hurricanes, cyclones or typhoons, the name depending on where you find yourself. With winds of over 100knots, these are to be avoided at all costs.

Routes

Cruising sailors prefer to sail down-wind if at all possible. The wind systems and the stormy seasons dictate the most frequently followed routes and the timing of ocean passages.

The Southern Ocean Route

The boldest circumnavigators avoid the Panama and Suez Canals and sail south across the Equator to reach the strong Westerlies of the Southern Ocean. They then usually sail east across the vast expanse of the Roaring Forties and pass south of at least three of the Five Great Capes: Cape Horn, on Isla Hornos, south of Tierra del Fuego in S.America, Cape of Good Hope, near the southernmost point of Africa (Cape Agulhas is the actual southernmost Cape but is not so dramatic) and Cape Leeuwin, the southwest Cape of Australia. These days, most sailors choose to pass south of all major land masses and so pass the SE Cape of Tasmania and the South Cape of New Zealand (on Stewart Island).

Cape Horn is usually passed during mid-summer: late December to early February. Sailors taking the Southern Ocean route will often brave huge seas and severe storms and will run the risk of icebergs near Cape Horn. On turning north again, the usual large high-pressure regions have to be negotiated either side of the Trade wind belts, as well as the Doldrums near the Equator. The shortest charted route is typically some 24000nm from Falmouth to Falmouth although in practice the distance logged will be rather greater. It is the route of the Vendée Globe single-handed race and of the Clipper and Volvo fully-crewed races and it is not for the faint-hearted.

Two of our circumnavigators chose this route. Both sailed alone. Both are women and one has done it three times (twice nonstop) plus a Trade Winds voyage, starting and finishing on the west coast of N. America.

The Trade Winds Route

Sometimes called the “Coconut Milk Run”, this is the route chosen by the majority of circumnavigators. From the UK, it runs down the Atlantic to the Canaries, then “south ‘til the butter melts” to meet the NE Trades. Then the course turns west towards the Caribbean, to reach one of the Windward or Leeward Islands. If time permits, many will spend at least a season in the Caribbean, possibly detouring up the eastern seaboard of N .America to Maine or Nova Scotia. Then through the Panama Canal, with a few heading north to Hawaii and on to Alaska and Canada, but most heading on across the Pacific via the Galapagos to the fabled South Sea Islands, aiming to reach New Zealand before the onset of the S.Pacific cyclone season. Mostly this is fabulous cruising, warm trade winds from aft of the beam, warm seas, almost endless sunshine. Throw in a string of unspoiled tropical islands with fabulous sea-life and friendly and welcoming locals and it’s no wonder those who can often spend a second year (or more!), (re)visiting Fiji before moving on to Australia via Vanuatu and New Caledonia.

Here the Trade Winds route splits. Some, intending to spend time in the Mediterranean, sail north through Indonesia and Malaysia, possibly to Thailand, across the northern Indian Ocean, visiting Sri Lanka, maybe southern India and the Maldives, before heading north towards the Red Sea and Suez. Conditions are generally easy but in recent years, the strong likelihood of pirate activity as the boats near the Arabian Peninsula has added a different kind of hazard. Following this route, the shortest distance to be sailed is about 26500 nm but most will have logged much, much more (in our case, 52,000nm!)

Others cross the southern Indian Ocean, visiting Christmas Island, Cocos Keeling, Rodrigues, Mauritius and Reunion en route to South Africa. Typically, winds are stronger here and the last part of the passage, across the Agulhas Current, as Richards Bay or Durban are neared, can produce some difficult conditions. Then up the South Atlantic to pick up the SE Trades, across towards Brazil through the Doldrums again and up towards Bermuda to find the Westerlies for the return across the N Atlantic. Often there will be a stop in the Azores, for centuries the meeting point of sailing ship routes to and from Europe, before the last 1200 nm or so to England. The shortest distance to be sailed on this route is about 29,500 nm.

The boats and their crews

On a circumnavigation, you soon realise that almost any well-designed and well-prepared yacht is capable of ocean cruising. The vast majority of our Circumnavigators sailed production yachts built in GRP and somewhere between 35’ and 45’ LOA. The largest was Express Crusader, 53’ long. All were capable of decent speeds, especially downwind. For most cruisers, however, speed comes second to sea-kindliness, ease of handling and comfort.

Fitting out for a circumnavigation is a time-consuming and often a costly business. It can add as much as 50% to the purchase price of the basic boat.

Most boats carried a crew of two, usually husband and wife. Some shipped extra hands for the longest passages. Most were in, or past, middle age, a fact dictated by the demands of jobs and family while younger. The younger ones have the priceless advantage of being able to do it again in later life and if they have children on board, the educational and personal development gain to them is immeasurable. But some sailed all or part of the voyage alone.

Equipment.

Apart from all the usual cruising gear and safety kit, most long-distance cruisers will have several ways of making electricity – solar panels, wind generator, water generator (towed or fixed), fixed or portable motor generator. A water-maker (desalinator) is very useful because there are very few taps supplying potable water, most aren’t alongside and rain often doesn’t fall when you need it. The smaller the crew, the more important is the autopilot and a wind vane is a valuable supplement to the power-hungry electric sort. Lots of spares are essential as chandleries are few and far between. Just one of Thor’s Thunderbolts can fry all your electronics and much else besides, so it is still prudent to have a sextant and a reliable watch somewhere safe (as well as wrapping a spare GPS and small laptop in aluminium foil, placed in a steel-lined oven or biscuit tin, whenever Thor is around). Shade is vital, big biminis are everywhere. Communications by SSB radio and/or satphone are essential for receiving weather forecasts, for email and for keeping in touch. Radio is especially useful for the many helpful cruisers’ nets and can be a vital aid to calling for assistance if disaster strikes mid-ocean. Few boats now do not have AIS (receiver, as a minimum) – it has become invaluable for safety at sea. Extra chain, a powerful electric windlass, long warps, storm sails, possibly a Jordan Series Drogue – the list is endless. Almost all of it will be needed.

This section covering the Circumnavigators and their achievements, is the work of Dick Moore, who coordinated the contributions of the authors of the logs, for the Centenary Book. As a Circumnavigator himself, Dick’s introductory text draws on his own expert knowledge of the great adventure.